1977 - 1992

1977 - 1992

Mayerling

My Brother, My Sisters

6.6.78

Métaboles

Nijinsky (reconstructions)

La Fin du jour

Playground

Gloria

Waterfalls

Isadora

Wild Boy

A Lot of Happiness

Verdi Variations

Quartet

Orpheus

Valley of Shadows

Different Drummer

Seven Deadly Sins

Tannhäuser (Venusberg)

Three solos

Requiem

Le Baiser de la fée

The Sleeping Beauty

Sea of Troubles

Soirèes musicales

The Prince of the Pagodas

Winter Dreams pas de deux

Winter Dreams

Poulenc pas de deux

The Judas Tree

Carousel

Mayerling

1978

Mayerling

1978

Mayerling was MacMillan’s fourth three-act ballet, completed after he had resigned as artistic director of the Royal Ballet in 1977. His interest in the Habsburg royal family and the demise of the Austro-Hungarian empire had been sparked by a 1974 book, The Eagles Die, by George Marek. The story of the double suicide of the Crown Prince and his young mistress at the Mayerling hunting lodge had been romanticised in several films; MacMillan wanted to show the social, political and personal pressures that might have driven the prince to such desperate measures.

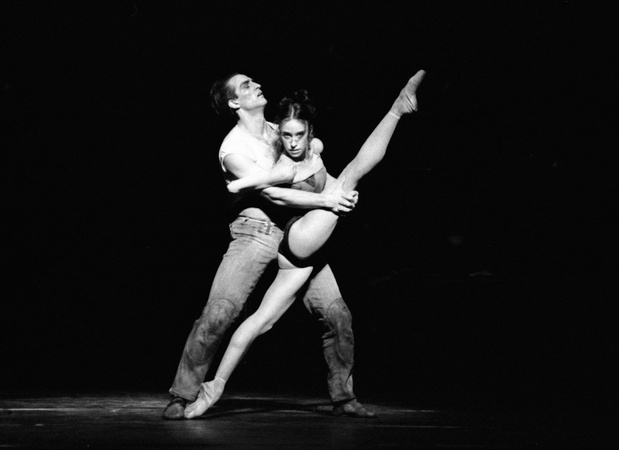

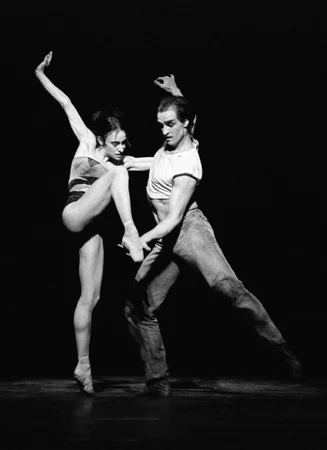

Edward Watson and Mara Galeazzi in Mayerling courtesy of Royal Opera House Archives.

He commissioned a scenario from Gillian Freeman, author and script-writer, who researched the period in depth, providing MacMillan with pen portraits of key figures in the Habsburg court and Viennese society. John Lanchbery, who had been the Royal Ballet’s chief conductor from 1960, suggested Liszt as an appropriate choice of composer. Not only would Liszt’s music provide the right atmosphere for the dramatic events (extracts from his Faust Symphony serving as a motif for Rudolf’s obsession with guns and death) but he had actually written piano music for Empress Elisabeth to play. Lanchbery arranged and orchestrated some 30 pieces of Liszt’s music as the score for Mayerling.

Lengthy preparations meant that the intended premiere in autumn 1977 had to be postponed. MacMillan had started work with Anthony Dowell as Rudolf, until he was injured early on and David Wall replaced him as the creator of the role. Rudolf is scarcely off the stage throughout the ballet, dancing seven major pas de deux with five different women. Mayerling was the first British ballet to make such demands of a male dancer in a leading role.

Mayerling starts and ends with a funeral. In a brief prologue, an anonymous coffin is lowered in the rain. Only in the epilogue will the audience realise that the corpse is that of Mary Vetsera, buried clandestinely in the cemetery of the Heiligenkreuz monastery, not far from the Mayerling hunting lodge outside Vienna.

After the sombre prologue, the first act opens with a state ball celebrating the marriage of the Crown Prince of Austro-Hungary and his Belgian bride, Princess Stephanie. Crowned heads, political dignitaries, courtiers and hangers-on file past before the ball begins. Although first-time viewers have little chance of identifying who they all are, significant players in the drama are on parade, including Mary Vetsera and her mother. Rudolf soon offends his bride by paying conspicuous attention to her sister, Princess Louise. He is reprimanded and it becomes apparent that he is a misfit in this pompous, hypocritical court. His dynastic marriage is intended to tame him and to produce an heir to the empire.

Georgiadis’s Act I set features tiers of stuffed dummies in ceremonial uniforms, reinforcing Rudolf’s awareness that he is always under surveillance. He is pressurised by four Hungarian nationalists to support their separatist cause; his complicity with them will spied upon and reported. To add to the intrigue, Rudolf’s former mistress, Marie Larisch, reminds him of her sexual claims on him. The Emperor interrupts their liaison and orders Rudolf to attend to his new wife.

On the way to the bridal chamber, Rudolf visits his mother in her apartments. Their encounter reveals his craving for her love and sympathy, but she is unable to respond. The real Elisabeth, married at 16 to the Emperor, had had little contact with her third child and only son, whose upbringing had been harsh. Unhappily married, Elisabeth found her life in the court barely tolerable. Both she and the Emperor had affairs. In the ballet, the relationship between mother and son is fraught with emotions both have to suppress.

Rudolf takes out his pain on his bewildered bride, terrifying her with a skull and a revolver before forcing himself on her. While Stephanie was prepared to submit to her marital duties in a dynastic marriage, she evidently had no idea what awaited her.

In the second act, Rudolf obliges Stephanie to accompany him to a tavern frequented by whores and their clients. She soon leaves in disgust, escorted by Bratfisch, Rudolf’s private coachman, who knows all about his master’s dissolute tastes. Rudolf, drunk, is entertained by his mistress, Mitzi Caspar, while the Hungarian conspirators amuse themselves. Rudolf hides with Mitzi from a clumsy police raid on the tavern. Afterwards, his mind disturbed, he tries to persuade Mitzi that they should commit suicide together. Repelled, she leaves conspiratorially with Count Taaffe, the Prime Minister, who knows that Rudolf is still in the tavern.

On the prince’s way out, he is met by Marie Larisch, who presents him to Mary Vetsera in a carefully contrived encounter. The real Larisch was Empress Elisabeth’s niece (albeit illegitimate) and Rudolf’s cousin. Married to a count, she had a place at court. She was a friend of Baroness Vetsera, Mary’s mother, a well-connected socialite. Mary, at 17, was already sexually ambitious.

In the next scene, Mary is sighing over a portrait of Rudolf when Larisch arrives on a visit to the Vetsera household. She sets up Mary as the next royal mistress-to-be by foretelling her future with a pack of cards. She encourages Mary to give her a letter for Rudolf.

Larisch finds a way to hand over the letter during Emperor Franz Josef’s birthday celebrations. All the court is assembled, including the Dowager Empress Sophie, Franz Josef’s formidable mother, and a pregnant Princess Stephanie. Elisabeth presents her husband with a portrait of his mistress, Katherina Schratt, who is by his side. While a firework display diverts the court, Elisabeth consorts with her lover, an English cavalry officer nicknamed ‘Bay’ Middleton after his horse. Rudolf is sickened by his parents’ duplicity and by the hopelessness of his own future. His mental state is deteriorating, damaged by disease (Rudolf had contracted syphilis) and morphine. Larisch provides a distraction by tempting him with Mary’s letter.

An assignation made, Larisch leads Mary to Rudolf’s bedchamber. Well-instructed or instinctively in tune with Rudolf’s fantasies, Mary confidently seizes the skull and pistol with which he had terrified Stephanie, and proves she is as sexually voracious as he is.

Act III opens with a royal shooting party in the snowy countryside, everyone elaborately dressed in furs to keep out the cold. As in all his three-act ballets, MacMillan starts each act with a crowd scene depicting the society in which his key characters move, before narrowing the focus to their personal dilemmas. During the shoot, Rudolf, evidently in a bad way, fires his rifle wildly, killing a bystander. The shot has narrowly missed the Emperor, and although Rudolf is suspected of aiming at him, someone else is arrested in a cover-up.

a clip from mayerling, A south bank special, 1978.

Back in his apartments in disgrace, Rudolf has been joined by Larisch, who attempts to console him. Empress Elisabeth discovers them together and angrily orders Larisch to leave. Larisch ushers in Mary Vetsera, who offers herself as an alternative to the morphine to which he has resorted. He proposes a suicide pact with her, to which she agrees. Her reason for so doing is left open. The real Mary was highly-strung, impulsive and self-dramatising. Perhaps, like adolescent girls through the ages, she romanticised the idea of death as the supreme act of love or defiance.

The final scene takes place in the hunting lodge at Mayerling. Rudolf dismisses his drinking companions and waits for Mary to arrive, escorted by Bratfisch. The coachdriver tries in vain to entertain the couple by dancing and juggling with his hat, but soon withdraws. Tension mounts as Rudolf, drugged with morphine and alcohol, engages Mary in a sexually frenzied pas de deux. He shoots her and then himself.

The epilogue shows how Mary’s corpse was taken by her uncles, propped up between them in her hat and coat, to the Heiligenkreuz cemetery at night. The double suicide had to be hushed up to protect the royal family and the state. Mary’s burial was kept secret and Crown Prince Rudolf was declared to have died of a heart attack – but rumours of suicide and even assassination soon spread and have never ceased to fascinate.

Mayerling’s premiere, somewhat inappropriately, was on Valentine’s Day 1978, at a royal gala. The audience gave it, and MacMillan, a prolonged ovation. Critics, invited to the next performance, applauded the boldness and originality of MacMillan’s approach. Mary Clarke in The Guardiandeclared that MacMillan had vindicated his decision to resign from the directorship of the Royal Ballet to devote himself to his true vocation. The world was short of choreographers who could make big narrative ballets for opera houses and who could show a great company to advantage. ‘It is a thrilling, moving theatrical experience’. Clement Crisp commented in The Financial Times that MacMillan had moved the three-act ballet from its 19th century structure and conventional fantasy figures into a form able to deal with the harsher realism of modern life. John Percival in The Times, a harsh critic of Anastasia and Manon, found that in Mayerling MacMillan had the full courage of his convictions: the set-pieces were relevant, the character-drawing clear and ‘even the most far-fetched of inventions [in the duets] worth the fetching’.

Percival and other critics recommended that cuts be made (Mayerling originally ran at three and a quarter hours). After the intial run, some of the scenes were trimmed – notably the hunting scene in the snow. The song, Ich Scheide (‘I am leaving’), sung by Katherina Schratt at the Emperor’s birthday party, was cut and then restored when its absence was found to unbalance the ballet. The stillness of the sequence allows the cast and audience time to register the relationships between the characters and the emotions seething beneath the formal etiquette of the court.

Mayerling’s reception in the United States, when the Royal Ballet took it on tour to the West Coast, was mixed. Audiences and local critics were impressed, but Clive Barnes in The New York Post (and on radio) and Anna Kisselgoff in The New York Timespanned it. Influential Arlene Croce in The New Yorker wrote a complex review that intermingled respect for what MacMillan had achieved with strong reservations about ballet taking on subjects she considered it ill-equipped to deal with, such as politics, disease and motives for suicide. Rudolf was ‘a titled creep forever Hamletizing around the house with a skull in one hand and a gun in the other’ but she summed up Mayerling as ‘this curious, crippled, provocative work by [a] master choreographer’.

The Metropolitan Opera House in New York initially refused to accept Mayerling as part of a Royal Ballet season in 1983. MacMillan threatened to withdraw all his ballets from the Royal Ballet repertoire if the Royal Ballet gave in. Mayerlingwas duly scheduled for just two performances, which were so over-subscribed that a matinee was added. East Coast audiences arrived by the coachload, their interest roused by the 1978 South Bank Show documentary about the making of Mayerling, which had been shown across the eastern seaboard by a TV company filling air time. Kisselgoff changed her mind in The New York Times, declaring that Mayerlingwas now a ballet that deserved to be seen in New York. It contained, she discovered, ‘unsuspected opportunities for great dancing as well as great acting’, and the Royal Ballet was dancing at a higher level than before. ‘It now has to be said that as a model of its own genre, [Mayerling] works completely on a level of sophistication and richness of detail’.

Although Mayerling has become a staple of the Royal Ballet’s repertoire, it is rarely seen in the United States. Only a few other companies dance their own productions of MacMillan’s ballet: they include the Royal Swedish Ballet, the Vienna State Opera Ballet and the Hungarian National Ballet.

First performance: Covent Garden, London, 14 February 1978

Company: Royal Ballet

Cast: David Wall, Lynn Seymour, Merle Park, Georgina Parkinson, Michael Somes, Wendy Ellis, Laura Connor, Graham Fletcher.

Music: Franz Liszt, arr. John Lanchbery

Design: Nicholas Georgiadis

Benesh notation score: Jacquie Hollander, Lyn Vella-Gatt (Master Score, 1978)

Video: Opus Arte (Mukhamedov, Durante, Bussell, Collier)

My Brother, My Sisters

1978

My Brother, My Sisters

1978

Shortly before the first performance of My Brother My Sisters, Kenneth MacMillan gave an interview to John Higgins, the arts editor of The Times. “Up to now with my story ballets”, he told Higgins, “I've been giving the spectators more and more information about the characters. Here, quite deliberately, I'm giving them less. It’s sufficient to say that there are five sisters and one brother; at the end of the work, which lasts about half an hour, you may be wondering whether they are related. I've based the ballet on real people, although fact and fiction are always blurred, and tried to realize their inner lives, not the ones they choose to show to the world. The idea has been with me for a considerable time. I read something, see something, forget it and then after an interval - four years in this case - it turns up again and is transformed into dance."

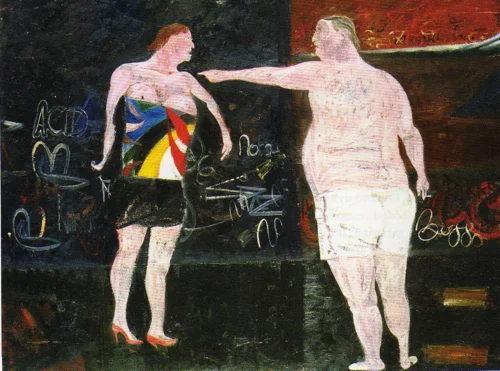

Costume designs for MBMS by Yolanda Sonnabend

The family of MacMillan’s ballet are, according to MacMillan’s programme note “set apart by landscape and circumstance, intelligence and passion”, the open moors beyond a graveyard in Yolanda Sonnabend’s settings suggestive of Bronte country. A further quote in the programme from A.E Ellis’s The Racksuggests that the children play in a graveyard, in which they themselves will one day lie. The reference to the Brontes is never explicit, but MacMillan did acknowledge it in a 1985 interview with Anna Kisselgoff of The New York Times. “It was Branwell (their brother) who was the hero of all their books. So my ballet became a ballet about a brother and all the sisters, about their fantasies. I didn’t want the public to know it was the Brontes.”

As in several other works MacMillan also explores here the intensely focused feelings of introverted groups. But in My Brother, My Sisters he pushes familial passions well beyond the point of crisis. As the family turns on itself, children’s games perverted through adult personality take on a psychotic logic. A highly sexual pas de deux depicts an incestuous relationship between the boy and the malign elder sister; younger sisters are coerced into an oppressive secrecy; the most vulnerable is endlessly bullied and in the end killed by her eldest sister. Throughout there is an outsider figure, a mysterious ‘He’, perhaps standing for MacMillan himself, who may be a dispassionate observer, or who may not exist at all.

“You can’t pretend to ‘like’ a ballet of this nature but goodness how you have to admire”, was Mary Clarke’s verdict in The Guardian. “And the final curtain, when the children finally realise their playacting has gone too far and death really has happened is terrifying.” For John Percival of The Times they were the most interesting cast of characters MacMillan had ever put on a stage: “all the more exciting to have such characters combined with an inventiveness of steps and phrases that exceeds even the youthful outpouring of his first professional ballet, Danses concertantes.”

“I do not know”, wrote Clement Crisp of The Financial Times, “if My Brother, My Sisters will become a ‘popular’ ballet; but its combination of action on two narrative levels, in that what we see at first glance is doubled by another and even more uneasy ‘inner’ narration, grips the mind, and demonstrates yet again MacMillan’s mastery as a choreographer able to explore the convolutions of the human psyche in exciting movement.”

First performance: Württembergische Staatstheater, Stuttgart, 21 May, 1978

Company: Stuttgart Ballet

Cast: Birgit Keil, Richard Cragun, Lucia Montagnon, Reid Anderson, Jean Allenby, Sylviane Bayard, Hilde Koch

Music: Arnold Schoenberg and Anton von Webern

Design: Yolanda Sonnabend

Benesh notation score: Georgette Tsinguirides and Eduard Greyling (1980). Master score

6.6.78

1978

6.6.78

1978

This was a piéce d’occasion celebrating the 80th birthday of Ninette de Valois, founder of the Royal Ballet. The performance at Sadler’s Wells (where, de Valois reminded the audience, “it all began”) was the last of series of celebrations over the summer months. The evening’s programme included de Valois’s The Rakes Progress. MacMillan’s new work in her honour quoted variously from de Valois’s ballets, its title 6.6.78 (a play on dancers’ counts) the actual date of de Valois’s 80th birthday.

Ian Spurling’s costumes and head dresses for the cast of twelve couples represented signs of the zodiac. Desmond Kelly and Marion Tait, in identically patterned body tights, were the Gemini twins (Gemini was de Valois’s birth sign). “Gemini’s appearance rightly imposed harmony on the apparent disorder of the comical other signs of the zodiac”, wrote Mary Clarke, in The Guardian, “and Marion Tait and Desmond Kelly danced their duets harmoniously.”

First performance: Sadler’s Wells, 26 September 1978

Company: Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet

Cast: Marion Tait, Desmond Kelly

Music: Samuel Barber, Capricorn Concerto

Design: Ian Spurling

Benesh notation score: Deborah Chapman (1978). Working score

Métaboles

1978

Métaboles

1978

Métaboles was created for the Paris Opéra’s Soirée MacMillan, the first time an entire evening by a British choreographer had been programmed there. The invitation had come from the then ballet director Violette Verdy and also on the programme was Four Seasons along with Song of the Earth.

In a programme note on Métaboles MacMillan quoted from Oscar Wilde’s Ballad of Reading Gaol (“Yet each man kills the thing he loves....) The curtain rises on five men in evening dress and a woman in long violet dress. Marie-Françoise Ridout described the action in Dance and Dancers. “Soon they rip off her long pleated dress and, like sadistic vampires, apply themselves collectively or singly to eating her”

Barry Kay had set high above the performance space a gigantically enlarged x-ray photograph of a human chest. From this Peter Williams, also of Dance and Dancers implied that “the area occupied by the dancers is by implication the stomach of a giant. Within it, a strange process of digestion is taking place.”

Clement Crisp of The Financial Times was also in the audience. “As in La Grande Bouffe, or the dinner scene in the film of Tom Jones, eating and eroticism are correlated. As the audience discovered, Métabole generated an obsessive emotional force. MacMillan uses an almost expressionistic manner at times (the men mime-eating, with hands rising and falling like pistons over a table) and the neurotic mood becomes very tense. Khalfouni and Bart were both excellent: Khalfouni, a pallid victim enjoying her fate, gave her role a morbid sensuality as she was handled in a variety of acrobatic/passionate lifts; Bart’s speed and impetuosity made the central male role as disquieting as that of the lunatic teacher in Flindt’s La Leçon.”

Scenic design for Métaboles ©Barry Kay Archive

Dutilleux’s score, an exploration of the metamorphosis of orchestral ideas (and with some obvious debts to Messiaen) had five sections: Incantatory, Linear, Obsessional, Torpid, Flamboyant. A dense and abstract work, it was a curious choice for MacMillan. Nonetheless, Peter Williams thought it contributed to the theatricality of the ballet. But for Ivor Guest, the historian of Paris Opera Ballet, Métaboles “proved one of MacMillan’s less happy creations – a disappointment partly assuaged by the acclaim awarded to the revival of his Mahler masterpiece, Song of the Earth.” Violette Verdy was pithier. “A bit much, even for the French”, she told Jann Parry.

First performance: Paris, 23 November 1978

Company: Paris Opera Ballet

Cast: Dominique Khalfouni, Patrice Bart, Patrick Dupond

Music: Henri Dutilleux

Design: Barry Kay

Benesh notation score: Grant Coyle (1978) Master score

Nijinsky (reconstructions)

1980

Nijinsky (reconstructions)

1980

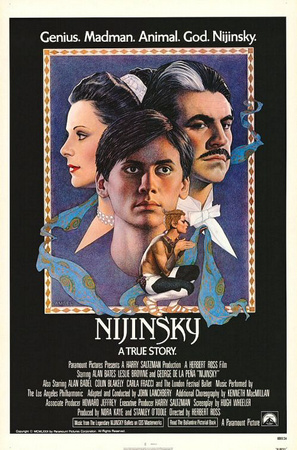

In 1978 the director Herbert Ross asked Kenneth MacMillan to choreograph the dance sequences for his film Nijinsky. In an interview for The Times, Ross told John Higgins: “We had to decide how good a dancer Nijinsky was. I suspect if we saw him today we would not be all that impressed. On the other had he was a marvellous choreographer, which is why Kenneth MacMillan tried to get as close as possible to the original, as we know it, of Jeux and Sacre du Printemps.” The film, which focused on the eighteen months between Romola de Pulszky’s introduction to Nijinsky and Diaghilev’s subsequent abandonment of him, was indifferently reviewed by cinema critics. For The Guardian’s Derek Malcolm it was “too long, too careworn and too lacking in directorial inspiration to survive its banal moments”.

One of the few dance writers to comment was Clive Barnes, who viewed it as an attempt at stylised biography by people “who know too much and care too much about the subject.” However there was universal praise for MacMillan’s reconstructions, which featured dancers from both The Royal and Festival Ballets.

Film poster for Nijinsky

In a column for The Times after the premiere Barnes wrote: “It (the dance) is exquisitely, and I use that word carefully, done. Time and again Ross and his dancers catch the precise image of one of those old Nijinsky photographs. Furthermore, with the exception of L'après-midi d'un faune, the visual reproductions by Nicholas Georgiadis of the original ballet designs are almost miraculous. Even more miraculous is the work of Kenneth MacMillan who, working from photographs, drawings and descriptions has produced “excerpts” from Nijinsky’s lost ballets – Jeux, which magically recreates all those photographs and Valentine Hugh drawings and Le Sacre du Printemps.” Monica Mason was cast as Maria Piltz, Nijinsky’s Chosen Maiden. MacMillan’s choreography was based on the archival evidence of the 1913 original and not on his own production for the Royal Ballet. However, the excerpts were just that, as Ross’s shot-list required short sections of choreography rather than sustained arcs of invention. Nonetheless, according to Jann Parry’s biography of MacMillan, Distant Drummer, his reconstructions of Jeux were particularly striking to those who watched them in the studio; MacMillan could not be persuaded to create a proper stage reconstruction afterwards.

Herbert Ross, the director, was himself a dancer and choreographer and married to the ballerina Nora Kaye, who was the film’s producer. In 1971 MacMillan had invited Ross to stage his choreographed version of Jean Genet’s The Maids for The Royal Ballet’s New Group.

Cinema release: 20 March 1980

Director: Herbert Ross

Screenplay: Hugh Wheeler

Cast: Alan Bates, George de la Peña, Leslie Browne, Alan Badel, Carla Fracci, Colin Blakely, Ronald Pickup, Ronald Lacey, Vernon Dobtcheff, Jeremy Irons, Frederick Jaeger, Anton Dolin, Janet Suzman

Dance sequences: Monica Mason, Valerie Aitken, Genesia Rosato, Ben van Cauwenbergh, Patricia Ruanne

Music: Igor Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring; Claude Debussy, Jeux

Design: Nicholas Georgiadis

La Fin du Jour

1979

La Fin du Jour

1979

In 1980 Kenneth MacMillan’s Gloria powerfully evoked the tragedy of the generation that went to war in 1914. La fin du jour, which he made a year previously, is a balletic snapshot of a successor generation - that of the 1930s - on the threshold of war.

The poet W.H. Auden called the 1930s “that low dishonest decade”, a view with which MacMillan may well have sympathised. La fin du jour has little of the elegiac about it. In a set of dances derived from fashion-plates of the period, MacMillan is using style to suggest content. His ballet shines a mirror to a leisured class on whose pleasures he seems very content to call time. MacMillan had intended naming the ballet L’Heure Bleue after Guerlain’s scent, fashionable in the 1930s, but had to change his plans when Ravel’s estate objected.

Birmingham Royal Ballet ©Bill Copper

La fin du jour begins with a beach party, the women in swim suits, the men in plus-fours and golfing caps. The focus is on two couples for whom there are introductory duets, a double pas de deux, solos and a seduction number. The second movement recalls the manipulation of the bridal couple in Rituals (1975). Two women, aviatrixes wearing goggles (recalling Amelia Earheart and Amy Johnson the aviation heroines of the day) are manipulated by five men apiece. Held high, they seem to pedal at the controls of invisible machines. In the final movement, as Peter Williams recorded for Dance and Dancers, the two male principals “bound about it shocking pink or apricot tail suits; the girls wear pleated chiffon culottes. There is much masculine activity, wide leaps covering the stage, and a sense of frenetic high spirits as darkness falls on the garden, seen through the door in the centre of the backcloth; the ballet ends as this door is closed on the world.”

For Alexander Bland of The Observer La fin du jour was “a cheerful and elegant pleasantry”; Arlene Croce of The New Yorker wrote “It’s a superficial ballet, but then it has superficiality as a subject” Several reviewers thought MacMillan’s seriousness of purpose subverted by the designer Ian Spurling’s high camp pastiche of 1930s fashion. “But it does”, wrote Mary Clarke for The Guardian, “get the period atmosphere of a carefree world when Elsa Maxwell gave parties and Gertrude Lawrence was the epitome of sophisticated elegance.” Clement Crisp, writing in The Financial Times, thought it a ballet far richer than it at first seemed. “It makes its points by hints, quick suggestions, but it does so with consummate sensitivity. It is a requiem for the douceur de vivre of an era, and it is nostalgically grateful for the 1930’s wayward charm.”

First performance: Covent Garden, London, 15 March 1979

Company: The Royal Ballet

Cast: Merle Park, Jennifer Penney, Julian Hosking, Wayne Eagling

Music: Maurice Ravel, Piano concerto in G Major

Design: Ian Spurling

Benesh notation score: Monica Parker (1979) Preliminary master score.

Playground

1979

Playground

1979

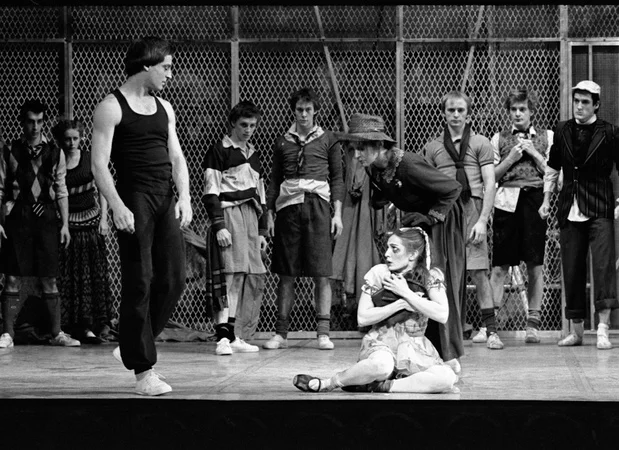

Playground was premiered at the 1979 Edinburgh Festival in a triple bill with Concerto and Elite Syncopations. The ballet is a social parable, which can initially leave its audiences with a sense of dislocation. It is not immediately clear if the characters seen on stage are children playing adults or adults playing children. It is the latter; the playground of the title is an asylum. MacMillan, who for several years had been undergoing psychoanalysis, is questioning where the balance of madness and sanity lies. In a mad world, he might be suggesting, the sane may appear mad.

As on several previous occasions, MacMillan began work with the Orpheus myth as a guide. Over the weeks of rehearsal Orpheus mutated into an intruder at a mental hospital. Yolanda Sonnabend’s wire-meshed courtyard is more suggestive of a prison than of a playground. Its inmates are adults acting out fantasies of childhood. For some, adults playing at children playing at adults, their fantasies are multiplied over as if in a hall of mirrors.

The intruder, a young man, becomes involved with the young woman, the Eurydice figure. As their encounter intensifies, she has an epileptic fit. The ‘vicar’ begins to pronounce funeral rites over her ‘dead’ body; the young man becomes violent and is attacked by the patients. He is then carried away in a straitjacket by hospital attendants (if so they be). The patients remove their children’s clothes and file off in drab institutional garb. The young man - a MacMillan outsider figure? - is left along banging his head against a wire fence.

copyright Leslie E. Spatt

Mary Clarke, writing in The Guardian, thought Playground “a mighty powerful piece of theatre, (using) a sparse vocabulary of movement with tremendous effect.” To Clement Crisp of The Financial Times Playground was both heart-rending and disquieting: “MacMillan’s style owes something to the manner of his My Brother, My Sisters, but Playground is even darker in mood though warmed by a compassion for the derelicts it studies. The reverberance of the characters and their relationships makes the piece far superior to any mere observation of madness.”

Twelve years later, in an interview with John Drummond for BBC Radio 3’s Third Ear, MacMillan acknowledged that Playground drew on his own distressed memories of his mother and her proneness to epilepsy. MacMillan admitted privately to Clement Crisp that it was a piece that he would liked to have seen performed by Pina Bausch’s Dance Theatre of Wuppertal.

First performance: Big Top, Edinburgh Festival, 24 August 1979

Company: Sadler’s Wells Ballet

Cast: Marion Tait, Desmond Kelly, Stephen Wicks, Judith Rowann

Music: Gordon Crosse

Design: Yolanda Sonnabend

Benesh notation score: Grant Coyle (1979) Working score.

Gloria

1980

Gloria

1980

MacMillan’s immediate source of inspiration for a First World War ballet was Vera Brittain’s autobiographical Testament of Youth. A poem from it, ‘The War Generation: Ave’ is quoted in the programme book whenever Gloria is performed. The ballet can also be seen as a testament to MacMillan’s Scottish father, who had been gassed in the First World War and who suffered the after-effects for the rest of his life. He never spoke of his experience in the trenches. He died of pneumonia when Kenneth was 17.

Although Poulenc’s Gloria in G is in praise of God in the highest, MacMillan intended it to be an elegy for young lives cut short or blighted by war. It could be seen as the third of his works contemplating mortality, set to vocal music: the earlier two are Song of the Earth (1965) and Requiem (1976). This time, unlike the previous occasions, no objections were raised by the board of the Royal Opera House to his choice of sacred music for a ballet.

all photographs copyright Leslie E. Spatt

MacMillan briefed his young designer, Andy Klunder, to look at photographs and paintings of the Great War, as well as memorial sculpture. The set is sparse, devastated, with entrances and exits over a ramp at the back of the stage. The men resemble soldiers whose uniforms, and flesh, have been torn off; their helmets recall the hats of medieval pilgrims. The women are dressed in silver-grey, with coiled ear-muffs that make them seem ghosts from a far-off past.

The two principal women embody aspects of Vera Brittain and all women who have suffered the loss of loved ones in wartime: one is the fearless girl, the other the woman in mourning. Brittain lost her brother and her lover in the war. The two principal men in the ballet are brothers-in-arms, unknown warriors. One survives the other, only to drop out of sight beneath the ramp on the last notes of the music.

The corps de ballet of women and soldiers serve as ritual celebrants, circling the stage at the beginning and end of the ballet. The four soloists are the personal expression of their anonymous suffering, dancing to the Latin words of the Catholic Mass extolling God’s mercy. The leading man who points at the audience during his last, defiant solo accuses passive spectators of acquiescing in death and destruction. The ballet is about the futility of all wars, not just the 1914-1919 Great War, which it was hoped, in vain, would end all wars.

Gloria was taken into the repertoire of the Stuttgart Ballet in 1983, and has since been performed by companies in the United States, Canada and Japan.

First performance: Covent Garden, London, 13 March 1980

Company: The Royal Ballet

Cast: Wayne Eagling, Julian Hosking, Jennifer Penney, Wendy Ellis

Music: Francis Poulenc, Gloria in G minor

Design: Andy Klunder

Benesh notation score: Diana Curry (1980). Master score

Television: ITV (Granada), 14 November 1982

Waterfalls

1980

Waterfalls

1980

In November 1980, Anthony Dowell helped Anya Sainsbury (Linden) to organise a ballet gala in aid of the Friends of One Parent Families. He took part in seven of the seventeen items on the programme. For the occasion Kenneth MacMillan choreographed a pas de deux in which Dowell partnered Jennifer Penney, set to Paul McCartney’s Waterfalls.

First performance: London Palladium, 30 November 1980

Occasion: Anthony Dowell Gala

Cast: Anthony Dowell

Music: Paul McCartney, Waterfalls

Isadora

1981

Isadora

1981

“Nobody could accuse Kenneth MacMillan of lack of courage”, began the review of the first night of Isadora by Alexander Bland of The Observer. In a two act work MacMillan pushed the boundaries of ballet theatre well beyond any previously accepted limits.

Isadora Duncan embraced free love, free expression and disdained ballet dancers as little more than trained acrobats. Nonetheless the dancers at the Mariinsky theatre in St Petersburg who saw her in 1904 were highly struck by the force of her stage presence and by a technique unfettered by the conventions of court ballet. She danced barefoot and, unlike ballet, her dancing acknowledged gravity and the body’s weight.

Tamara Rojo in Isadora, The Royal Opera House 2009

When MacMillan made Isadora to open the Royal Ballet’s 1981 season, his choice of subject made strange sense. For Duncan dance was liberative, and of a piece with her radical politics, a view with which MacMillan could straightforwardly empathise. MacMillan aimed to reshape dance as a medium of social comment. And his work was increasingly attracting interest from a new audience which had not hitherto been much engaged by dance. So much so that ITV decided to show Isadora in prime time and the current affairs broadcaster David Dimbleby wrote an approving profile of MacMillan for The Times.

He was not concerned, MacMillan told Dimbleby, whether audiences thought Isadora was ballet or not. “I am not worried by the style. I just want people to feel that they have had a good night at the theatre. I am steeped in classical dancing, but this is 1980 and I cannot go on doing what they did in the last century. I’ll do anything to break away.”

MacMillan’s focus was less on Duncan the dancer than on her tumultuous personal life; her affairs with Ellen Terry’s illegitimate son Gordon Craig; with the Russian poet Sergei Essenin whom she married; with the sewing machine millionaire Paris Singer; and the devastation of losing her three children to early death, one in childbirth, the other two when the car in which they were passengers ran into the River Seine. MacMillan’s innovations in multi-media story telling went well beyond the techniques he had deployed in Anastasia and Seven Deadly Sins. The use of the spoken word in aid of the dance was both extensive and appropriate; Duncan herself was a polemicist, for whom the dance and the word were all of a piece. MacMillan borrowed from Duncan’s Victorian lecture-demonstration technique and this device is deployed throughout the ballet.

At the premiere Merle Park danced the role of Isadora, with the actress Mary Miller (who had attended the same dance school as MacMillan as a child) speaking lines from her autobiography. The ballet’s most profound episode of choreographic imagination came with Isadora and Paris Singer dancing their grief for the death of their children after they drown in the Seine. In a compelling pas de deux, each by turn falls and picks the other up with silent screams, as they fumble and circle about the stage. The ungainliness underscores their grief. Of this section Clement Crisp later wrote: “The rawness of their shared despair, and also the phenomenal outlines of the movement partake of the force of Picasso's brush-strokes in Guernica. I sensed that beyond this expressive point academic choreography could not go. That audiences were profoundly moved by this harsh, beautifully ugly exposition of grief, and responded to the drama of its imagery, cannot be doubted, even in a ballet as diffuse and as flawed in structure as this Isadora.”

Richard Rodney Bennett’s score provided pastiche music for the dancer's public appearances, and used Bennett's own music, his native voice, for Isadora’s private life and its relentless sexual turmoil. ''I must say that even though I've never worked as hard on any project as I have on this, I had the time of my life writing the music for Isadora”, he told The New York Times “There was a time, when I was 20 years old and a student of Pierre Boulez, when I couldn't think beyond the notes. But now, I'd much rather write about sex.''

Isadora’s two acts each lasted some 75 minutes. Only a minority of critics were persuaded of its cumulative effect. For Mary Clarke of The Guardian, Isadora needed “absolutely drastic cutting”, while Clement Crisp, of The Financial Times, its most fervent advocate, conceded that MacMillan’s treatment was “too generous in incident.” MacMillan himself was dissatisfied with the outcome and, in the months that followed, cut some twenty minutes from its length. In March 2009, the Royal Ballet restaged a single-act one hour version of Isadora

But in 1981 Michael Billington of The Guardian, the doyen of London’s theatre critics, thought it an important artistic breakthrough. “What worries me”, he wrote, “is that the kind of people who make up Broadway and Covent Garden audiences are no so stuck in a kind of artistic lockjaw that (unless the critics give their seal of approval) they seem unable to enjoy anything that breaks yesterday’s mould. What we need is not simply a new theatre: we also desperately need a new audience.”

First performance: Covent Garden, London, 30 April 1981

Company: The Royal Ballet

Cast: Merle Park, Mary Miller, Derek Deane, Julian Hosking, Derek Rencher

Music: Richard Rodney Bennett, Isadora

Design: Barry Kay

Scenario: Gillian Freeman

Benesh notation score: Monica Parker/Adrian Grater (1981) Working score.

Television: ITV, 23 February 1982

Wild Boy

1981

Wild Boy

1981

Wild Boy was Kenneth MacMillan’s first commission from American Ballet Theatre since Journey in1957. MacMillan based his concept on Gordon Crosse’s score Wildboy, a concertante piece for clarinet with cimbalom and seven players. Cross had been inspired by François Truffaut’s film L’enfant sauvage. This in turn was based on Jacques Itard’s early nineteenth century account of how he tried to educate a boy found in a forest, and who had been brought up by animals. On the face of it, Wildboy offered intriguing possibilities as a dance score; MacMillan was encouraged by his previous experience of having choreographed another Crosse score Play Ground for Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet. Crucially for MacMillan, so drawn to the outsider motif, a child of nature might be portrayed as the ultimate outsider.

Kenneth MacMillan in rehearsal with Mikhail Baryshnikov for Wild Boy

In MacMillan’s new ballet, the Wild Boy was danced by Mikhail Baryshnikov, by then the artistic director of ABT. The choreographic focus was equally on the captors, two loutish men and a woman whom they possess sexually. The contrast between The Boy’s pure state in nature and the men’s violence is overwhelming. The woman has sex with The Boy. He in his turn is appalled by a homoerotic kiss between the two men. Finally The Boy is left alone, contaminated by contact with humankind and rebuffed both by humans and by the animals who had nurtured him.

Arlene Croce of The New Yorker struggled with the scenario. “Is it the Woman’s or the Wild Boy’s story that is being told? Our sympathies are attached to him, but she is an innocent too. How then does it happen that sex with the Wild Boydoesn’t revive her, but drains him? The moment of truth is reached when the two brutes are made to kiss each other accidentally and he falls back in horror at this revelation of homosexuality. It drives the Wild Boy to drink after which the animals of the forest sniff him disdainfully.”

Watching the animals, Clive Barnes, writing for The Times, was reminded of the clowns in MacMillan’s early ballet Laiderette (1954), who had similarly stood and watched a betrayal, disillusionment and the failure of an outsider to come in from the cold. There was no doubt, according to Barnes, that MacMillan could still “choreograph like a genius” but that from the outset he was hamstrung by the score’s “relentless mediocrity”. A Washington Post critic Alan Kriegsman complained that MacMillan “seem(ed) to expect the public to swallow the grossest forms of erotic exhibitionism and cynical bombast on the ballet stage as if they were the height of aesthetic daring. Anna Kisselgoff of The New York Times thought The Wild Boy more sketch than finished work, “but its very rawness is what makes it stimulating”.

First performance: Kennedy Center, Washington D.C, 12 December 1981

Company: American Ballet Theater

Cast: Mikhail Baryshnikov, Natalia Makarova, Kevin MacKenzie, Robert La Fosse

Music: Gordon Crosse

Design: Oliver Smith (costumes), Willa Kim (scenery)

Scenario: Gillian Freeman

Benesh notation score: Monica Parker (1981). Preliminary master score

A Lot of Happiness

1981

A Lot of Happiness

1981

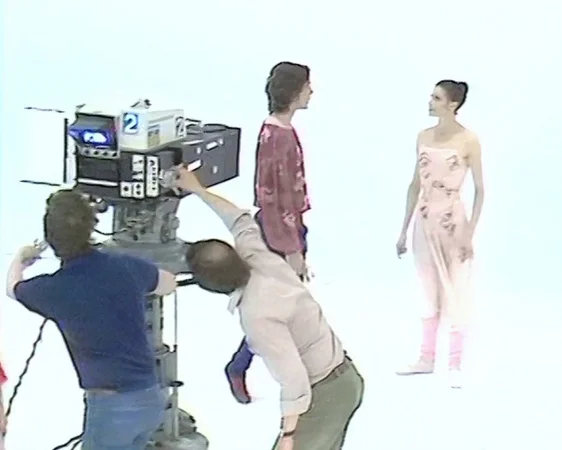

"It's like doing a giant jigsaw puzzle. You have to find each little piece - and it has to be the right piece. This is a game. And I like this game." Granada Television had asked Kenneth Macmillan to choreograph a new ballet specifically for television, from scratch. The director Jack Gold and a camera team then followed the making of the piece - the rehearsals at the Northern Ballet School, and the final TV studio recording - over five days. The result was a documentary, A Lot of Happiness, shown on the ITV network. Macmillan worked with two of his favourite dancers – Birgit Keil and Vladimir Klos, both from Stuttgart Ballet. The choreography was to music from Chopin and Gershwin. Jack Gold questioned MacMillan as cameras eavesdropped on the rehearsals. For the Chopin pas-de-deux, MacMillan’s starting point was the Orpheus legend – “but the audience needn’t know that”. This gave him a set of working images and moods, determining a progress from uncertainty to sadness to rejection. “In the end this may not have all this meaning. It may be just a pas-de- deux. But it’s helping me find the steps.”

The programme’s title came from MacMillan’s instruction to Keil and Klos to show ‘a lot of happiness’. Peter Williams, writing for Dance and Dancers, was struck by the accidents of the creative process. “Why did he choose a particular step at this moment? Why this position rather than that? Because here Birgit Keil’s arms defined a satisfying sculptural ‘hole’; because there what MacMillan had been aiming for didn’t work and what Keil had done instead was far better. There was one sudden, accidental inspiration with ravishing results. After MacMillan had got Klos to throw Keil into an airborne double tour, he hit on the idea of the catch becoming a clinch and a kiss. ‘A double turn, which is very gymnastic, ending in a realistic kiss. I want to shock the audience’. This raised the interesting question of the appeal of MacMillan’s choreography in its mingling of stylised classical steps with everyday gestures or movements anyone would recognise. ‘I think I use more naturalistic gestures than most other choreographers.’ ”

The satirist Clive James, the then TV critic of The Observer, was struck by the Chopin pas-de-deux’s layer of unintended poignancy; Poland’s Communist regime had declared martial law in the week the programme was broadcast. He praised the documentary as ‘brilliantly directed’. “The completed job was a fully adequate television tribute to that most organic of artistic events, the MacMillan pas de deux. In fact, if MacMillan’s dance numbers got any more organic, you would have to ring the police. ‘I’m trying to get a bit sexy now,’ he confided, tying Vladimir and Birgit into a reef-knot.”

First performance: Granada TV, 15 December 1981

Participants: Birgit Keil, Vladimir Klos, Kenneth MacMillan, Philip Gammon, Monica Parker, Jack Gold

Music: Chopin, Piano Sonata No. 3; George Gershwin, Three Piano Preludes

Director: Jack Gold

Design: Deborah Williams

Video: Granada TV, running time 57’ 03”

Verdi Variations

1982

Verdi Variations

1982

In March 1982 the Italian ballet ensemble Aterballetto, founded by Amedeo Amodio, was one year old. It opened its second season with an adventurous programme which included MacMillan’s Verdi Variations. This was an extended duet, a showpiece for two of the company’s frequent guest dancers Elisabetta Terabust and Peter Schaufuss, and would be incorporated into Quartet, which MacMillan was then creating for Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet.

For John Percival of The Times, who was at the first performance, this was MacMillan’s “most successful creation for some time... an extended duet of pure virtuosity”. He continued: “Terabust never looked better than she does in her solos, full of pretty little steps, and in the many off-balance poses of the adagio sections. Schaufuss, besides partnering her with unfailing strength and friendly attentiveness, tackles such wildly whirling leaps in his solos that there is no defining or even describing them; yet the most prodigiously abandoned moments are all carried off with astonishing accuracy.”

First performance: Reggio Emilia, Italy, 1 March 1982

Company: Aterballeto

Cast: Elisabetta Terabust, Peter Schaufuss

Music: Verdi, String Quartet in E minor (first movement)

Benesh notation score: Monica Parker (working score) 1982

Quartet

1982

Quartet

1982

Kenneth MacMillan created Quartet in several stages and did not wait until it was completed before staging its constituent parts. Quartet began life in February 1982 as Verdi Variations, a showpiece for Elisabetta Terabust and Peter Schaufuss, which they performed in a programme with the Italian company Aterballetto. MacMillan choreographed it to the first movement of Verdi’s String Quartet in E minor.

Next, MacMillan choreographed Quartet’s second movement; this time for Sadler’s Wells Ballet and arranged for string orchestra by Barry Wordsworth. It was now a double pas de deux and a late addition to the programme performed at Sadler’s Wells in March 1982. There it replaced a promised new MacMillan work, Noctuaries, to a commissioned score by Richard Rodney Bennett, with whom MacMillan had already collaborated on Isadora. But MacMillan, sensing that he was not making progress, abandoned Noctuaries and concentrated instead on Quartet.

John Percival of The Times had already praised the Terabust/Schaufuss duet as MacMillan’s “most successful creation for some time.” To this Mary Clarke, writing in The Guardian commented on the Sadler’s Wells performance that “MacMillan’s writing in his most fluent, easy classic style boded wonderfully well for the finished work.”

MacMillan completed Quartet a month later and it was performed at a gala in Bristol in aid of Wells Cathedral.

First performance: Hippodrome, Bristol, 7 April 1982

Company: Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet

Cast: Sherilyn Kennedy, David Ashmole, Galina Samsova, Desmond Kelly, Marion Tait, Carl Myers, Sandra Madgwick, Roland Price

Music: Giuseppe Verdi, String Quartet in E minor

Design: Deborah MacMillan

Benesh notation score: Monica Parker and Grant Coyle (1982). Preliminary master score.

Orpheus

1982

Orpheus

1982

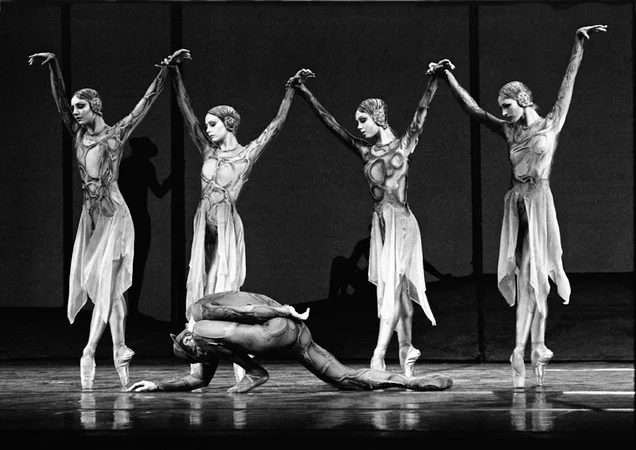

Kenneth MacMillan was fascinated by the Orpheus myth and it is one to which he repeatedly returned in his choreography. In June 1982 The Royal Ballet staged a triple bill to celebrate the centenary of Igor Stravinsky’s birth. The programme comprised Fokine’s The Firebird, Nijinska’s Les Noces and a premiere, Kenneth MacMillan’s Orpheus. Stravinsky’s score was originally commissioned for George Balanchine and Ballet Society in 1948; MacMillan’s interpretation was his eighth – and final - Stravinsky ballet.

MacMillan follows the main thread of the Greek myth, albeit with interpolations of his own. The ballet opens with the dead Eurydice being lowered from high above the stage into her tomb; only then does the music begin. As Orpheusmourns her and rages at her untimely death, the Angel of Light and the Dark Angel contend for his soul. The Dark Angel leads Orpheus across the River Styx where he is led blindfolded to Eurydice. Then follows their rapturous reunion; but when they finally lay eyes on each other, Eurydice is swiftly borne away and Orpheus is torn to pieces by The Furies. The Dark Angel claims Orpheus’s body, but the Angel of Light escapes with his lyre, which in the final scene he loses to Apollo. In an apotheosis, the two lovers are reunited in death as Apollo plucks the strings of Orpheus’s lyre.

“MacMillan uses the particular qualities of his principals to the greatest advantage”, wrote Stephanie Jordan for Dancing Times. “Jennifer Penny is introverted and glacial, as she is rocked by a river of bodies over the Styx and in her nervous, light little solo, bold and consuming as she wraps herself about Schaufuss in the epicentral pas de deux. Schaufuss, making his Royal Ballet debut, is impassioned yet easy and articulate in execution of an array of virtuoso bounds and turns and jerky wiggle walks that depict the emotion and turmoil of Orpheus, generous and elastic as he plucks his lyre in the song of consolation in Hades.”

Design for a Fury by Nicholas Georgiadis

Earlier in the year MacMillan had choreographed Verdi Variations for Peter Schaufuss and Elisabetta Terabust. It was this experience that led MacMillan to request that Schaufuss be a guest at Covent Garden for Orpheus. There was considerable enthusiasm for his ‘incredible virtuosity’ (The Observer), while for Clement Crisp in The Financial Times, MacMillan’s use of Schaufuss was never gratuitous; “the dance feeds from his bravura but also enhances it.”

Nicholas Georgiadis’s dramatic set featured golden ladders leading to a black underworld inhabited by insect like creatures which might have come from outer space. The skeleton echoing body-tights of the masked angels of dark and light reminded one reviewer of the predatory Bird Woman in House of Birds. Georgiadis’s designs for Orpheus subsequently won him the Evening Standard award for Outstanding Contribution to Dance.

First performance: Covent Garden, London, 11 June 1982

Company: The Royal Ballet

Cast: Peter Schaufuss, Jennifer Penney, Wayne Eagling, Ashley Page, Derek Deane, Bryony Brind, Genesia Rosato, Michael Batchelor, Antony Dowson

Music: Igor Stravinsky, Orpheus

Design: Nicholas Georgiadis

Benesh notation score: Monica Parker (1982) Preliminary master score

Valley of Shadows

1983

Valley of Shadows

1983

Valley of Shadows was Kenneth MacMillan’s portrayal of the fate of an Italian Jewish family under fascism, Nazi occupation and the horrors of the death camps. Inspired by Georgio Bassani’s novel The Garden of the Finzi-Continis and the film of the same name by Vittorio de Sica, it was controversial for its choice of subject. While the family’s fate was only alluded to in the film, MacMillan’s scenario makes it explicit. After its premiere the appropriateness - even the possibility - of depicting the events of the Holocaust in balletic terms was hotly debated.

The action moves back and forth in time between the luxuriant and secluded garden of the Finzi-Contini family and the concentration camp where many of them will die. Exiled from the local tennis club from which they are barred by Mussolini’s race laws, a group of young people instead play in the garden. While at first they show little awareness of what is happening to their elders, a sense of menace builds strongly. The romantic and sexual entanglements of the garden are intercut with scenes at the camp to which the ballet’s characters are brought successively to confront their destiny.

In what many who saw it described as a shattering performance, Alessandra Ferri danced the role of the young and flirtatious Micol around whom the story revolves. In her seclusion and self-centeredness she is careless of what is happening to all around her. The ballet is a study in her increasing isolation and she is the final character to meet her fate. As Mary Clarke of Dancing Times recorded, “The moment of real terror which seizes Ferri at the end of the third garden scene when the men have gone and the guards claim her is shattering. More than any of the others, she conveys, through the choreography MacMillan has set for her, the hell she has been through before her bruised and battered little body is thrown into the camp.”

In a choice of music that recalled the three-act Anastasia, MacMillan used Tchaikovsky’s melancholic sweetness to depict the carefree world of the garden with, for the death camps, Martinu’s darker and dislocating sound world.

After the first performance of Valley of Shadows, as Robert Penman of Dancing Times recorded, there was as there was a moment’s silence in the Royal Opera House followed by vigorous and prolonged applause. One member of the cast, Derek Deane, enthused in a Guardian interview about “the power you find in MacMillan’s steps”. From the newspaper critics Valley of Shadows drew reactions perhaps more dividedly partisan on the issue of its merits than any of MacMillan’s works since Anastasia. On one note, John Percival of The Times spoke for all. “Alessandra Ferri is exactly right for the young heroine. Not only is her supple pliant body ideal for the ingenious contrived adagios that are MacMillan’s speciality, but she has enough flair and commitment to convey emotion with her face even in the most back-breaking moments.”

First performance: Covent Garden, London, 3 March 1983

Company: The Royal Ballet

Cast: Alessandra Ferri, Sandra Conley, Julie Wood, Derek Deane, Guy Niblett, David Wall, Ashley Page

Music: Bohuslav Martinu, Double Concerto; Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Hamlet Op 67 - Entr’acte, Elegy; String Sextet in D Major ‘Souvenir de Florence’, Op. 70 – 2nd movement

Design: Yolanda Sonnabend

Benesh notation score: Monica Parker (1983) Working score.

Different Drummer

1984

Different Drummer

1984

“It is not an easy ballet”, The Guardian’s critic Mary Clarke said of Different Drummer “but it should be seen especially by people who think ballet is just Swan Lake”. In his choice of title MacMillan was quoting from Henry Thoreau’s Walden. “If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music he hears, however measured or far away.”

Different Drummer was inspired by George Büchner’s play Woyzeck, the story of a soldier and his descent into insanity. MacMillan told the writer Rachel Billington that he had arrived at his subject when he produced Strindberg’s play Dance of Death in 1983, an experience which re-stimulated his interest in expressionism. He also knew Berg’s opera Wozzeck and this clearly influenced his choice of composers for Different Drummer - Berg’s teacher Arnold Schoenberg, along with Berg’s contemporary in the Second Viennese School, Anton Webern. MacMillan had similarly drawn on Schoenberg and Webern when choosing music for My Brother, My Sisters (1978).

Written in 1836, Büchner’s play, based on an actual murder case, was a powerful indictment of the exploitation of the poor by the military and medical establishments of the time. Its antihero is forced to earn extra money to support his mistress Marie and their child by performing menial jobs for his captain and taking part in degrading medical experiments. As Woyzeck’s health deteriorates, Marie turns her attentions to a handsome drum major. Woyzeckconfronts the drum major who beats him up. Persecuted and humiliated, Woyzeck stabs Marie to death before he drowns himself in a bath.

A programme note read: “Kenneth MacMillan wishes to thank Yolanda Sonnabend for her contribution to the creation of this ballet.” But five days before the premiere MacMillan made a decision to abandon her designs and kept only her costumes. Instead Different Drummer was performed on an almost bare stage stripped back to a few flats with the decor from the opera Andrea Chenier, then in production at Covent Garden, decked around the walls, while a large bath stood centre stage.

The ballet, like Büchner’s play, is fragmentary, but mesmeric in the accumulation of these fragments. It opens with Woyzeck and Andres his fellow-soldier dutifully marching while on guard. Then Woyzeck’s torturers arrive and MacMillan progressively reveals the humiliations visited on him by the Doctor and the Captain; his relationship with Marie and his cuckolding by the Drum Major; Woyzeck’smounting despair and hysteria; the inexorable descent into murder and a suicide. These events are rendered through the prism of Woyzeck’s tortured psyche. As the ballet ends, Woyzeck’s and Marie’s corpses are prepared for an autopsy; the Doctor and the Captain wheel mortuary trolleys triumphantly across the stage. But in a suggestion of an apotheosis - and mirroring Schoenberg’s score - Woyzeckand Marie seem transfigured; united in another world while their bodies are left in the hands of their earthly tormenters. However, the suggestion of transfiguration did not survive in MacMillan’s subsequent reworking of Different Drummer for the Deutsche Oper ballet in Berlin and the Royal Ballet’s later restagings.

MacMillan draws variously on Büchner’s religious referents. In the original, Marie, plagued by guilt at her relationship with the Drum Major, reads the Biblical story of the woman taken in adultery. She comforts her (and Woyzeck’s) illegitimate child by telling him a fairy story. When she returns to the Bible, she finds there the story of Mary Magdalen. Balletically, Marie, as it were, becomes Mary Magdalen, washing the feet of a soldier, who reveals his identity with a crown of thorns. Elsewhere, a simple duet for Woyzeck and his friend Andres is suggestive of a piet´.

The layers of choreographic movement echo the ballet’s title; the perfect drills of the corps de ballet, soldiers who march with elegantly pointed feet; a more individual language for Andres, Woyzeck’s friend; the Doctor and the Captain are expressionist ciphers. But for Woyzeck there is graphically distorted movement – worried backward jumps, shoulder spins - which speaks his alienation.

Different Drummer is a complex, difficult work with which several critics struggled. But to the author Rachel Billington it had “the compulsive, nightmare feeling of a painting brought to life.” Billington also noted afterimages of the First World War. MacMillan, she sensed, was exorcising demons; railing at the fates that had so reduced his own father, who had been gassed in the conflict. Clement Crisp of The Financial Times spoke for the work’s many advocates when he characterised the ballet as “uncomfortable, haunting, brave”.

First performance: Covent Garden, London, 24 February 1984

Company: The Royal Ballet

Cast: Wayne Eagling, Alessandra Ferri, Stephen Jefferies, Guy Niblett, David Drew, Jonathan Burrows, Jonathan Cope, Antony Dowson, Ross MacGibbon, Bruce Sansom, Stephen Sheriff

Music: Anton Webern, Passacaglia for Orchestra, Op. 1; Arnold Schoenberg, Verklärte Nacht, Op. 4

Design: Yolanda Sonnabend

Benesh notation score: Monica Parker (1984) Working score.

Seven Deadly Sins

1984

Seven Deadly Sins

1984

Kenneth MacMillan’s production of The Seven Deadly Sins for Granada television was his third treatment of the Brecht/Weill “ballet with songs” and was substantially different from the other two. For this production, MacMillan added a prologue to music from Brecht/Weill’s The Threepenny Opera showing Anna arriving at Ellis Island in New York Harbour along with other refugees from Europe. Two, danced by Birgit Keil and Vladimir Klos of Stuttgart Ballet, are denied entry to the New World.

The Dancing Anna was Alessandra Ferri, then a twenty-year old, whose star was then strongly in the ascendant at the Royal Ballet. The more worldly Singing Anna was the Australian soprano, Marie Angel.

For Mary Clarke, writing in The Guardian, MacMillan’s staging was assured and definitive. “Cabaret style and sinful dance come easily to him; visually it was stunning”. To John Percival of The Times it seemed that MacMillan’s choreography had a natural affinity with television with the Ellis Island prologue making it possible for Derek Bailey, who directed, to establish the silent-movie style of the production.

“This permits MacMillan to write in roles for Birgit Keil and Vladimir Klos, two exceptionally photogenic and expressive dancers. After that, the main asset of the show is Alessandra Ferri, her ubiquitous innocently sexy presence ravishingly displayed in a series of exiguous garments by Yolanda Sonnabend, responding to every misadventure with dogged enthusiasm.”

First performance: Granada TV, 22 April 1984

Company: The Royal Ballet

Cast: Alessandra Ferri, Marie Angel, Leslie Brown, David Taylor, Birgit Keil, Vladimir Klos, Mary Miller, Stephen Roberts, John Tomlinson, Robert Tear, Robin Leggate, Peter Baldwin, Robert North, Christopher Bruce, April Olrich, Kim Rosato, Wayne Aspinall, Peter Salmon

Music: Kurt Weill and Berthold Brecht, Seven Deadly Sins

Director: Derek Bailey

Design: Yolanda Sonnabend

VIdeo: Granada TV, running time 51’ 14”

Tannhåuser

1984

Tannhåuser

1984

This was the second time that Kenneth MacMillan had choreographed the Venusberg ballet in Act One of Tannhaüser (the first was in 1955). Here, Venus was a night club hostess in slinky leather and sequins, who oversaw a celestial floor show choreographed by MacMillan. The production made some edits in the music; there was a cut from the overture into the Venusberg music, which allowed MacMillan’s choreography to begin seamlessly; the absence of the bacchanal also meant that the ballet was relatively short. The four dancers came from London Contemporary Dance Theatre.

Elijah Moshinsky, the producer, located this Tannhaüser at the edge of the world; the action taking place on a round platform in the midst of a blackness into which the heroine, Elisabeth, departed for her death and Venus for her eclipse.

Tom Sutcliffe, writing for The Guardian, thought the floorshow “sexy in the abstract, cleverly turned, but not stirring.” For Jann Parry of The Observer, the ballet looked “like a visual of Purgatory. The four dancers who depict the pleasures of the flesh are deathly pale, subhuman creatures, unadorned except for a dark stream down their spines. They copulate aridly in unison, twisting their supple bodies into almost abstract shapes. Small wonder that Tannhaüser, voyeur rather than participant, wants to leave.”

First performance: Covent Garden, London, 25 September 1984

Company: The Royal Opera

Dancers: Christopher Bannerman, Linda Gibbs, Ross McKim, Kate Harrison

Music: Richard Wagner

Design: Yolanda Sonnabend

Producer: Elijah Moshinsky

Three Solos

1985

Three Solos

1985

“A Celebration of Dance” was the billing for the Contemporary Dance Trust’s fund-raising gala at Covent Garden in July 1985. For the occasion Kenneth MacMillan choreographed three solos for past and present members of London Contemporary Dance Theatre, Christopher Bannerman, Linda Gibbs and Ross McKim. The solos were severally called Without Ceremony, Untitled and Descent.

First performance: Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, 11 July 1985

Company: Contemporary Dance Trust Gala

Cast: Christopher Bannerman, Linda Gibbs, Ross McKimn

Music: Johann Sebastian Bach, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Georg Phillipp Telemann

Requiem

1986

Requiem

1986

Kenneth MacMillan’s Requiem for American Ballet Theatre, set to Andrew Lloyd Webber’s score, was premiered during ABT’s annual winter season in Chicago. Lloyd Webber took his inspiration from a story in The New York Times during the rule of terror of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia about a boy forced to choose between killing himself or his sister.

Requiem is divided into nine sections, each one corresponding to a section of the Mass for the dead. “The boy’s dilemma of having to kill his sister, of always being haunted by that horror, is the image from which I’ve tried to recreate the dance”, MacMillan wrote in a programme note. His founding image was of a pietà; that of the boy holding his sister’s limp body and rocking it back and forth. Throughout the ballet this image is repeated, amplified and varied on. The sister was danced by Alessandra Ferri, recently arrived at ABT from The Royal Ballet, while the role of the boy, although created for Mikhail Baryshnikov, was danced at the premiere – and subsequently – by Gil Boggs (Baryshnikov had recently had an operation for a knee injury). Three couples, backed up by a corps, seemed to act as alter egos, elaborating the anguished emotions of brother and sister.

At the premiere Sarah Brightman sang Requiem’s soprano role and reaction to the work in the local press was warm. “Theatrically successful ...more than the sum of its parts”, was The Chicago Tribune’s verdict. “Dancing against Yolanda Sonnabend's nebulous transparent splattered curtains and hanging coils -which Tom Skelton's lighting transforms brilliantly into everything from a concentration camp to blood or fire - the corps and the soloists kept up the emotional pitch”, wrote Anne Kisselgoff, The New York Times’ critic. For the dance historian Beth Genné who attended the first night for Dancing Times, Requiem showed MacMillan “responding in a deeply felt, musically sensitive way to a huge, and at times, undisciplined score that juxtaposes some very heavy-handed orchestral and vocal effects with moments of real pathos and power.

First performance: Auditorium Theater, Chicago, 7 February 1986

Company: American Ballet Theatre

Cast: Alessandra Ferri, Gil Boggs, Cynthia Harvey, Susan Jaffe, Leslie Browne, Ross Stretton, Kevin McKenzie, Clark Tippet

Music: Andrew Lloyd Webber, Requiem

Design: Yolanda Sonnabend

Benesh notation score: Monica Parker (1985). Preliminary master score

Le Baiser de la Fée

1986

Le Baiser de la Fée

1986

Kenneth MacMillan first choreographed Le Baiser de la fée in 1960; twenty six years later he revisited the ballet, making changes for a new generation of dancers. The first performance of the revised work was at a gala for the Royal Ballet Benevolent Fund along with two works from his years in Berlin, Concerto and Anastasia. The performance was dedicated to the memory of Barry Kay, who had recently died of complications caused by AIDS and who had designed Anastasia along with seven other of MacMillan’s works.

Baiser de la Fée design by Gary Harris

To Mary Clarke of The Guardian who had seen the original ballet in 1960 it seemed that MacMillan had “retained much of what was written for Lynn Seymour – those swirling, circular lifts, those limpid descents when the foot melts into the ground above a bent knee, the sorrow of her exit after desertion. And how marvellous to see MacMillan writing again in a purely classical style.” John Percival of The Timesalso noted the close resemblances to the 1960 version. “I cannot understand why the earlier version was unsuccessful. It had only 24 performances between 1960 and 1965, yet it was blessed with superb performances and one of the most beautiful decors ever created for the Royal Ballet, a set of marvellous abstract landscapes by Kenneth Rowell.” In fact, Kenneth Rowell’s designs, which had been destroyed, were themselves the reason why the earlier production was set aside. They were so complex that there were few other ballets with which for technical reasons it could be programmed.

In his earlier production, MacMillan’s preoccupation was with the betrayed Bride, the figure in the ballet left truly alone (“she’s the one who is lost”) after the fairy entices her husband away. But in the 1986 version, MacMillan aligned himself with Stravinsky’s original intent; that the ballet is an allegory, the Fairy’s fatal kiss marking out the artist from other mortals.

There was little warmth for Martin Sutherland’s designs. In The Observer Jann Parry dismissed the set as ‘unimaginative’. “He succeeds in evoking neither the Fairy’s ‘Land beyond Time and Place’, nor the village from which she claims her initially reluctant hostage.”

By common consent Le Baiser de la fée is Kenneth MacMillan at his most exquisitely classical. But the production did not last long in repertory. Maria Almeida, who danced the Bride, has coached Isabel McMeekan in The Bride’s Solo; the video is on this site’s Media area.

A new production is to be performed by Scottish Ballet in 2017 and designed by Gary Harris.

First performance: Covent Garden, London, 8 May 1986

Company: The Royal Ballet

Cast: Fiona Chadwick, Sandra Conley, Jonathan Cope, Maria Almeida

Music: Igor Stravinsky, Le Baiser de la fée

Design: Martin Sutherland

2017 Design: Gary Harris

Benesh notation score: Vergie Derman (1986)

The Sleeping Beauty

1986

The Sleeping Beauty

1986

Unlike The Nutcracker and Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty did not feature prominently in the American ballet canon. It was essentially the preserve of visiting foreign companies; the Royal Ballet, The Kirov and the Bolshoi. Such performance tradition as did exist in the United States was that of American Ballet Theatre. It had previously staged an abbreviated version known as Princess Aurora and at one point had in its repertory a full-length staging by Mary Skeaping. This last used the designs created by Oliver Messel for the reopening of Covent Garden in 1946

Kenneth MacMillan’s is the first American Beauty of major importance. He based the production, which was overseen by Monica Parker, on the notation created by the Russian ballet master Nikolai Sergeyev, the source on which the Royal Ballet’s production is based. MacMillan’s own contributions were the Garland waltz, variations for Prince Desiré and Princess Aurora in Act II, the journey to the castle and the Awakening, and the Jewels divertissement.

In an interview with The New York Times ahead of the New York premiere, MacMillan explained how The Sleeping Beauty made him aware of ''the value of the pas de deux - how it can be the climax of an entire ballet. Petipa's choreography also taught me the importance of timing. For me, The Sleeping Beauty is more than a fairy tale. It's a tribute to a style of living. It celebrates fine manners and good breeding.'' Of his own largely traditional production, he said ''If choreography already exists for a scene, one should keep it. When there are missing pieces in the choreographic jigsaw puzzle, then, of course, they have to be filled in.''

The production budget was one million dollars and the sets designed by Nicholas Georgiadis were built in London. The ballet’s time span was located between the mid seventeenth and mid eighteenth centuries with Georgiadis’s costumes based on paintings by Van Dyke and Tiepolo a hundred years apart. ABT’s rehearsal process was riven with tension; Mikhail Baryshnikov, the company’s artistic director did not share MacMillan’s reverence for the traditional text and MacMillan found his work constantly interferered with by the Russian ballet mistress who was in charge of ABT’s classical repertoire.

Despite all this, the production was a success. For Robert Greskovic writing in Ballett International, MacMillan’s Beauty was “primed to advance ABT to a new plateau.” For David Vaughan in Ballet Review it was “a British production of a nineteenth century Russian ballet danced in twentieth century American style”; he applauded the company’s dancing, “which showed a great improvement” and this he credited to MacMillan. For Joan Acocella in Dance Magazine, it was a “grand and decorous staging ...stylistically consistent which created that atmosphere of sweet security in which the classical dream – that truth is simple, knowable and beautiful – could for three hours come true.”

MacMillan’s production remained in American Ballet Theatre’s repertory for eighteen years, before coming to English National Ballet in 2005.

First performance: Auditorium Theater, Chicago, 7 February 1986

Company: American Ballet Theatre

Cast: Susan Jaffe, Robert Hill, Leslie Browne, Victor Barbee, Marianna Tcherkassky, Johan Renvall

Music: Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky, The Sleeping Beauty

Choreography: Marius Petipa (with additions by Kenneth MacMillan)

Design: Nicholas Georgiadis

Sea of Troubles

1988

Sea of Troubles

1988

Sea of Troubles is a short work which Kenneth MacMillan created for Dance Advance, an ensemble of former members of the Royal Ballet. In a programme note for the premiere MacMillan explained his inspiration.

“I have taken as a starting point the effect of the death of Hamlet’s father without a literal telling of the play. With the appearance of his father’s ghost, and Hamlet’s realisation of the need for revenge, his tormented world became a nightmare”

MacMillan reshaped the narrative for six characters; Hamlet, Gertrude, Claudius, the ghost of Hamlet’s father, Ophelia and Polonius. The dancers in turn represent the various characters depicted; Batchelor, Maliphant and Sheriff variously as Hamlet, Claudius, Polonius, or the Ghost; and Crow, Jackson and Styles as Gertrude or Ophelia. The approach is filmic – almost Noh-like; the scenes sharply intercut, the characters haunted by a ghost and their own guilt.

Yorke Dance Project performing Sea of Troubles 2016 ©Charlotte MacMillan

Kenneth MacMillan with the original cast of Sea of Troubles (Dance Advance) copyright Neil Libbert

The piece was a gift from MacMillan to its performers, his only condition being that it be recorded in Benesh notation. It was choreographed to be danced in smaller venues and - unusually in a MacMillan work - the dancers were barefoot. The Guardian’s critic Mary Clarke, who saw the premiere, wrote “For setting there is just a cream lace curtain which will serve as arras. Costuming is simple: black trousers and white shirts for the men, soft grey dresses for the women. When cloaks, paper crowns or a chaplet of flowers are added, the dancers , in turn become royal or mad Ophelia; when a plastic shroud envelopes a figure, we know Hamlet’s father is dead or Ophelia drowned...I found the work totally engrossing, marvellously theatrical.”

Sea of Troubles toured widely in 1988 and 1989, was briefly in the repertoire of Scottish Ballet in 1993, before being performed by a company led by Adam Cooper with dancers from English National Ballet in 2002 and again in 2003. In 2017 it was revived by Yorke Dance Project and performed at The Royal Opera House as part of the 25 year anniversary of MacMillan's death.

- First performance: Gardiner Centre, Brighton, 17 March 1988

Company: Dance Advance

Cast: Michael Batchelor, Susan Crow, Jennifer Jackson, Sheila Styles, Russell Maliphant, Stephen Sheriff

Music: Webern/Martinu

Design: Deborah MacMillan

Benesh notation score: Jane Elliott (1988). Working score

Soirées Musicales

1988

Soirées Musicales

1988

Soirées musicales was created for the Royal Ballet School’s summer performance at Covent Garden in 1988. The score, a suite of Rossini melodies which Britten arranged, has often been used for dance. Dana Fouras and Gary Shuker were the central couple in a cast of twenty six. The performance launched the career of Tetsuya Kumakawa, already a precocious talent. The role danced by Shuker was created on Alastair Marriott, who by the time of the performance was on tour in Australia with the Royal Ballet.

“In their braided jackets and jaunty headgear both corps and soloists suggest a military air” wrote Angela Kane for Dancing Times. “The clipped staccatos and linear groupings, the picked up pas de bourrées and the precision of head inclinations are reminiscent of Ashton’s Scènes de ballet. In the male duet, though, the circling grand jetés of Benjamin Tyrrell and the double saut de basques of Kumakawa are more akin to the ‘spotlight’ solos in Balanchine’s Stars and Stripes.”

First performance: Covent Garden, London, 21 July 1988

Company: The Royal Ballet School

Cast: Dana Fouras, Gary Shuker, Tetsuya Kumakawa, Benjamin Tyrrell

Music: Benjamin Britten (after Rossini), Soirée musicale

Design: Ian Spurling

Benesh notation score: Julie Lincoln (1988)

The Prince of the Pagodas

1989

The Prince of the Pagodas

1989

Britten’s ballet score for The Prince of the Pagodas was commissioned in 1954 for a three-act ballet by John Cranko, mounted by the Sadler’s Wells Ballet in 1957. For the scenario, Cranko had conflated a number of fables: Beauty and the Beast, The Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella and King Lear. He apparently regarded the plot as a thread on which to hang a series of divertissements. Britten provided more music than Cranko found he required but refused to allow the score to be cut or reordered.